Valerie Conn is executive director of the Science Philanthropy Alliance

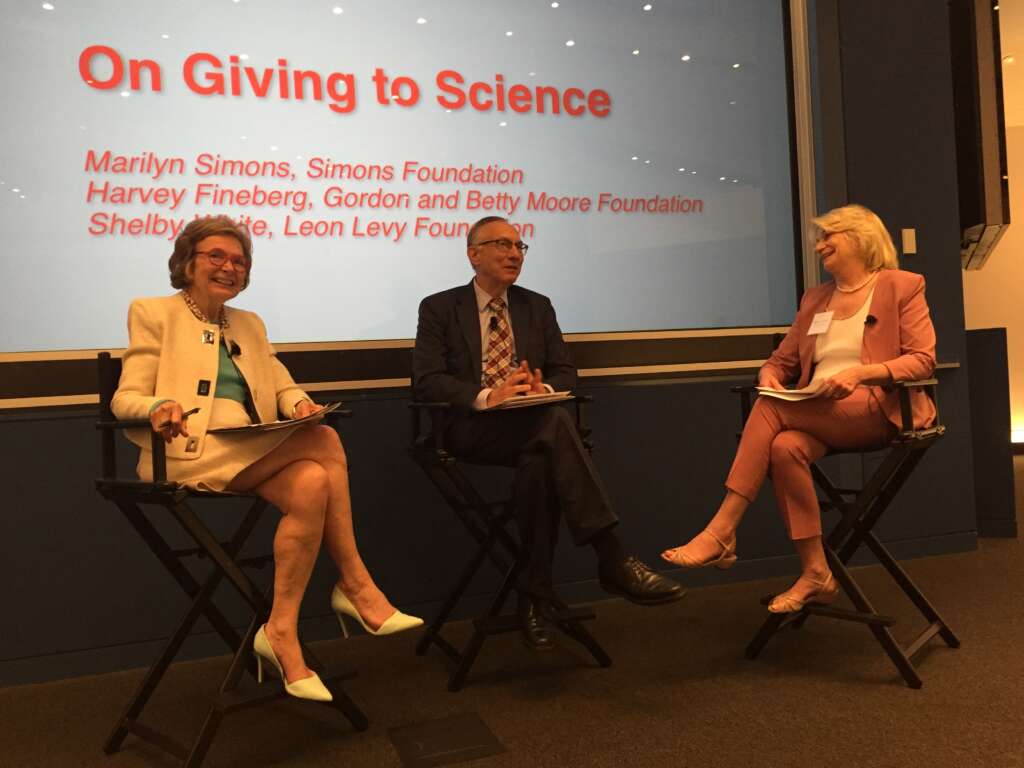

Twice a year, the members of the Science Philanthropy Alliance gather to talk about the successes and challenges they face in their discovery science giving, and to learn from each other. At our meeting in June, Marilyn Simons, president of the Simons Foundation, moderated a panel with Harvey Fineberg, president of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and Shelby White, founder of the Leon Levy Foundation. They articulated contrasting approaches that foundations take in their giving, which I wanted to share.

One key factor that influences the culture of a foundation is whether their founder is still actively engaged in the work of the foundation. Gordon and Betty Moore are no longer involved in the day-to-day decision-making at their foundation, but they developed a statement of intent for the leaders and staff, outlining core values and motivations for their philanthropy as well as what they hope to accomplish and how they intend the foundation to operate. These detailed instructions provide a concrete set of principles for the foundation staff to follow, allowing the foundation to adapt and change with the times while keeping true to its founders’ principles.

The Moore statement of intent includes four filters: 1) whether a question of possible support is really important, 2) if it can make an enduring difference, 3) if it is measurable, and 4) if it contributes to a portfolio effect.

In contrast, New York based philanthropist Leon Levy left no explicit instructions for his foundation, only telling his wife Shelby White to start one, and that the foundation should end fifteen years after she passes away. So Shelby created giving guidelines to look at problem-solving with long-term payoff, focusing on areas of support that are important and can make an enduring difference – choosing to “plant trees that would never mature in our lifetime,” as Shelby said in the meeting. She has also directed the foundation to allocate money so the foundation doesn’t leave any programs unfunded when it ends.

(l to r) Shelby White, founder of the Leon Levy Foundation, Harvey Fineberg, president of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and Marilyn Simons, co-founder of the Simons Foundation, discuss their approaches to philanthropy.

Deciding what to fund

Another important part of philanthropy is choosing what to invest in, a topic that came up as Marilyn asked about the way each foundation pursues projects. While both the Moore and Leon Levy foundations fund institutions and individuals, the process of deciding what or whom to fund varies.

For the Moore Foundation, identifying projects of opportunity starts with engaging its science advisory board, which helps generate and assess potential areas of interest.

The Leon Levy Foundation, however, often chooses projects based on the personal interests of Shelby and Leon. Science, for example, became an area of dedication after Leon met Torsten Wiesel, former president of Rockefeller University and Nobel Prize winner. Most of the foundation’s science giving is centered in New York City, and other giving includes Shelby’s significant support to Brooklyn (her hometown) institutions. The foundation is also interested in putting together an advisory board that can provide independent evaluations of its science investments.

Both foundations value the support of young people through grants and fellowships.

Measuring success

Marilyn then raised a difficult question: how do foundations measure success? Her own background is in economics, so she is metric-oriented, but there are no simple answers.

“Jim [Simons] likes to say that you know when you see it or you can just feel the difference,” she said, referring to how to determine impact. Marilyn later explained that Jim believes that in the case of pure science or mathematics applications are usually so far off that no metrics can apply, but the foundation’s staff scientists and advisors can be depended upon to know good work when they see it.

For Shelby, it’s impossible to measure a return on investment in a lot of cases.

“We want to have some measure, guidelines on whether what we’re doing is right,” she said. “But not so much with the metrics, leveraging, and return on investment — especially since a lot of what we give is in the humanities. How do you measure what it means if you give a wing to a museum? You cannot measure how this might change a life — for kids to go to a museum and look at art.”

While the Moore Foundation uses metrics as one form of measuring the effectiveness of a program or investment, Harvey also noted that metrics aren’t everything.

Harvey discussed his philosophy that philanthropy is the venture capital for society. “When you’re in a line of business where you are succeeding all the time, you’re not ambitious enough,” Harvey said. “You have to take those risks, and risk implies occasional failure.”

At the end of the day, philanthropy is about finding opportunities that “others won’t or can’t support,” as Harvey said. It’s about giving back to society for the long term. And now, with the administration’s proposal of significant cuts in basic research funding, private philanthropy’s interaction with basic research matters more than ever. Only through pursuing discovery science research can we begin to explore applied science.

Regardless of the differences in their approaches to funding, the Leon Levy Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the Simons Foundation are dedicated to identifying and implementing effective ways to support discovery science research. They and other Alliance members will continue to seek and share these lessons with other foundations and funders and with the scientific community.